I'm Keeping The CDs!

CD Mom is keeping the CDs. Today Katie Wojciechowski shares why she is too.

We don’t run ads here. On Repeat is made entirely possible through the support of our paid supporters. You can back independent ad-free music journalism for less than $1 a week.

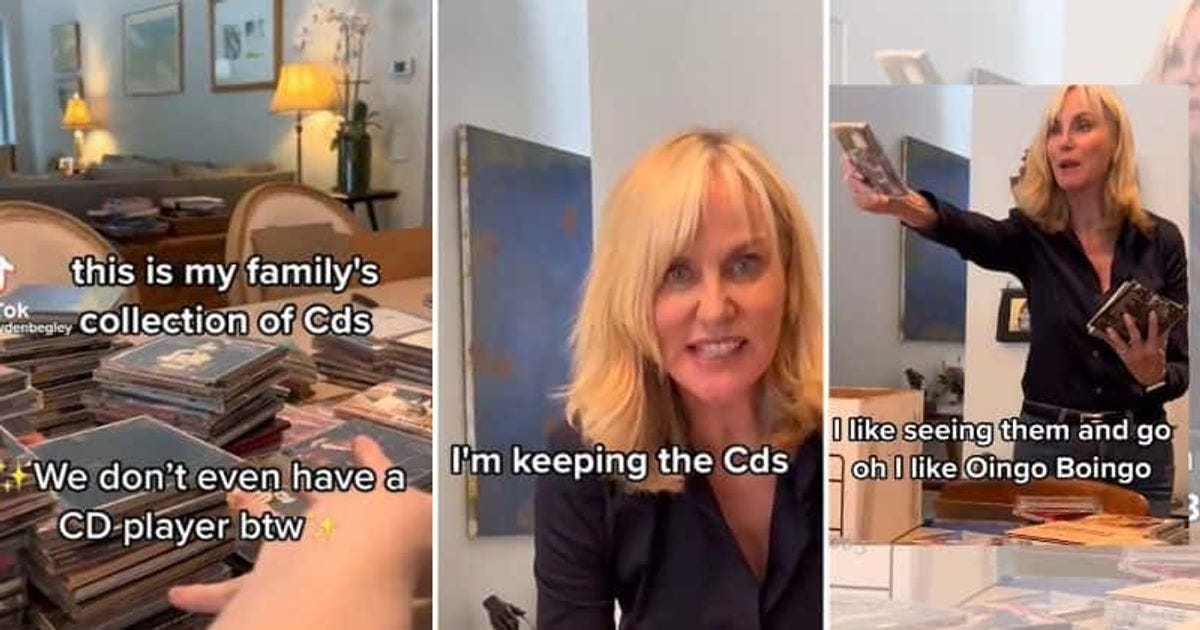

A meme is good when it’s funny. A meme is great when it’s funny and relatable. That’s why the one pictured above of “CD mom” refusing to part with her collection has gone so viral. A lot of us have been in her shoes.

In my case, I swapped tapes for CDs and then swapped CDs for songs on iTunes (or ripped from sketchy places like Limewire and Kazaa). I spent most of the early 2000s getting rid of my physical media, and I spent most of the 2020s buying it back.

It’s fun to point and laugh at CD mom, but I’m just pointing back at myself whenever I do.

It resonated with

as well. Katie writes the fantastic—and criminally infrequent— Good and Good For You newsletter. Originally focused on Paramore, it has evolved into what she describes as the soundtrack to her life and includes playlists, reviews, love notes, and emotional chaos—and [exploring] exactly what it is that you get when, as the poet Hayley Williams once said, you let your heart win.She’s also finishing a book on the band and is currently shopping it around. If you or someone you know is in the publishing world, get in touch!

When she’s not writing, she can be found on Twitter, posting about the Austin music scene or The Portland Trailblazers (#RipCity).

Katie’s thoughts are below the jump. I’m excited to hand her the keys to the truck and hope you’ll enjoy reading her story as much as I have. And I’ll bet it resonates with you, too.

~KA

I’m listening to Ben Folds’ album Songs For Silverman, and according to its Spotify footnote, it came out on April 11, 2005. However, it wasn’t until 2008 that I purchased a used copy of Songs For Silverman on CD from Buybacks, FKA CD Warehouse—the little resale media store tucked away in the strip mall off South Mopac. CD Warehouse was manned by surly hipsters whose scorn I eventually came to think of as a rite of passage.

There’s a TikTok that’s made the rounds on Twitter a few times recently. It begins with a young person pointing to a big table full of CDs and saying, “This is my family’s collection of CDs. And what I’m trying to help them understand…”

Suddenly, the camera pans to the person’s mom cutting in with a bellow: “I…DONT…CAAAARE!” Her blue eyes flash beneath bottle-blonde bangs, and she continues: “I’M KEEPING THE CDS! I got rid of my albums, and they came back! I’m not letting this…I’m not doing this again!”

“Okay, but here’s the thing,” her kid attempts, “is that if you like a song on here, I could play it faster than you’d be able to open this…”

“No, because I don’t REMEMBER the songs that I like!!” cuts in Mom, waving a CD around wildly, quickly devolving into fervent nonsense. “I like seeing them and going OH! I like Oingo Boingo! I like Anita Baker! I wanna hear her! I won’t remember that she’s even alive[??].”

I am that mom. She and I—analog twin flames. I’m keeping the CDs.

I’m not alone. CDs are making a comeback. For one thing, Gen Z’s thrifting population has discovered that CDs are a cheap way to expand one’s music taste, catalyzed, of course, by the Y2K aesthetic’s dominance. Music critic Steven Hyden recently tweeted: “A personal goal is to popularize CDs just enough that I can vibe with people on social media about the awesomeness of CDs without driving up the price of CDs on the secondary market,” a goal I wholeheartedly support.

The future of art-- of the things that make life bearable and even beautiful–-is a dizzying void. CD Mom feels it. I feel it. You likely feel it too. Having your music in a format you can physically hold and own has never been more crucial. It’s a sense of cosmic security.

Modern music buyers have several choices when it comes to physical format. I love vinyl, but there’s something profoundly approachable in how portable and affordable CDs are. I love tapes, but unlike tapes, CDs are basically ubiquitous—if a record exists, it probably exists as a CD. I love that CDs are the size of a hand. Ready to be held, to be touched, like a rosary. To be guarded and revered with CD Mom’s religious fervor.

If music makes life worthwhile and stirs our hearts, then it is indeed a kind of religion, a conduit for the salvation we so desperately crave. And, like any religion, music requires devotion, and commands our attention through physical artifacts. Any good disciple of music will tell you that collecting music’s physical totems—vinyl, cassette tapes, CDs—is one of the most sacred and potent avenues of worship.

Back in 2008, I bought Songs For Silverman on CD from CD Warehouse–- not because I hadn’t heard it before, but because I already loved it. I kept a scrupulous list of albums I wanted on my shelf in colorful squares, in sturdy plastic. I’d spend my evenings and weekends browsing Austin’s music stores, working my way down the list, using my allowance to build out my library.

While CDs were technically my first musical medium (I got a few for Christmas as a kid, etc.), I came of proper music-listening age right at the dawn of the iPod, so by the time I was going out to buy CDs myself, it was an active format choice, not the default music medium. I did it because I loved feeling the insert in my hands, scouring the liner notes for secrets, and admiring the neat, shiny rows.

I also did it because I was desperate to qualify as a real music fan. The online narrative of the mid-aughts was that iTunes was killing music and that there was a moral advantage to owning physical media. But more than anything else, it was fun to collect and keep the music I loved the most—or the music I thought I ought to love the most. Any given CD in my collection at the time was likely to encompass at least a bit of both.

Songs For Silverman drew me in with its gravity of intricate piano melodies and wry confessions, but pricked my teenage Evangelical conscience with its cheeky heresies. I couldn’t bring myself to listen to “Jesusland,” Folds’ critique of American Christianity, and I hated when he used the Lord’s name in vain—the CD contains more than its fair share of “goddamns.” But god damn it all if I wasn’t a little bit in love with the way his hands tumbled down the keys on “Landed,” a song I practiced on my parents’ piano over and over and over with no real aim, no goal other than to physically feel the song that moved me in such a way. For me, to love a song is to physically touch it on keys, on strings, in my throat, in my hands. To hold it, to make it mine.

I haven’t bought a CD in years, except for two. One of them was Court and Spark, by Joni Mitchell. And the other one was Blue, by Joni Mitchell. They’re both essential to me, and when she pulled her music from Spotify in 2022, I bit the bullet and bought the CDs so I could get my fix in the car. But the occasion got me questioning why I don’t buy CDs regularly anymore. I’ve been thinking a lot about the impermanence of Spotify—among its other myriad pitfalls, like its failure to pay artists what they’re worth, or its shitty user interface. Even if (when) I choose to overlook these flaws and keep Spotify as my primary music repository, there’s always the threat of all my precious playlists disappearing entirely if something ever happened to the company. My lifeblood, heart of my heart, the music that keeps me going on my darkest days—it’s all at the mercy of some floundering corporation’s servers. I don’t like that. It feels profane.

Best Buy stores have started clearing their shelves of all physical copies of movies and TV shows, and my chest is tight when I read about it—to know that perhaps our time of stocking up on physical media is limited, and in an age where streaming services can revoke access to anything at any time. What I’ve always theorized is beginning to take effect: that if you can’t hold it in your hand, it’s at the whim of stakeholders. Physical objects, however, are not so easy to take away from us. My reverence for Buddhist philosophy would tell me that true holiness lies in the ability to let go, to own nothing, keep nothing. But my heart, ever greedy, ever grasping, says otherwise. I want to keep my music forever.

Toward the middle of Songs For Silverman sits “Late,” Ben Folds’ tribute to the deceased Elliott Smith. He solemnly reflects that it’s too late now to tell Smith, who died by suicide in 2003, how much his music had meant to him. The minor chords cascading into soft sevenths toward the end of each chorus seem, to my ears, like a tribute to Elliott’s own melodies.

Over plaintive piano notes, Folds confesses to Smith’s ghost:

Under some dirty words on a dirty wall

Eating takeout by myself

I played the shows

Got back in the van and put the Walkman on

And you were playing

In the CD playing in his Walkman, Folds’ friend lived on, in a way. A CD is a harbor for memories. A link to the past and an insurance policy for the future. Sturdy and real, a reminder—in the face of the future's yawning void—that there really are some things we can keep.

Thank you to Katie for letting me share this here, and thank you for being here!

Kevin—

I feel bad for my daughter and her friends. They have never known what it's like to hunker by an FM radio with a finger on the record button of a tape deck just so they can get a static-filled copy of the new Duran Duran single. They don't go to record stores because every song they have ever wanted is at the end of a Google search. They don't understand the thrill of flipping through mountains of used CDs and finding a gem in the pile. Physical media is more than music--it's memory. It's moments. It's a record of who you are and were.

50% of the vinyl I own belonged to my parents before me. I love knowing that my music taste was shaped by these physical discs that also blew my mom's teenage mind. It's a generational connection that's hard to replicate.